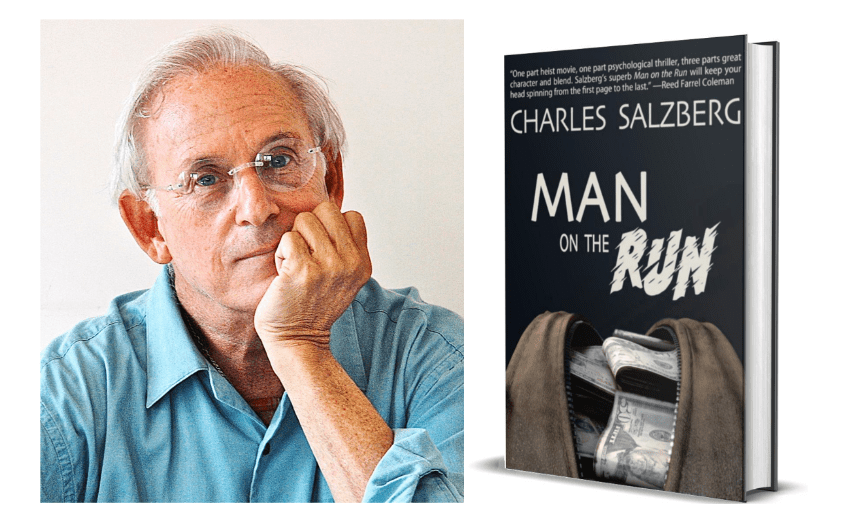

In “Man on the Run,” award-winning author and former Hunter College professor Charles Salzberg drops readers into the tumultuous world of a mastermind fugitive named Francis Hoyt. This crime novel, soon to be released on April 17, is a continuation of a series that follows a character who has an obsession with winning. The Envoy’s Culture Reporter Panagiota Chasan sat down with Salzberg to talk about his new book ahead of its release.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What specifically about “Man on the Run” do you believe would speak most to Hunter students and intrigue them to read it?

The main character, Francis Hoyt, is not a good guy. He’s ambitious, he’s arrogant, and he’s reckless and manipulative. And I’m not saying that would be more appealing to someone in college rather than someone older, but I think we’re all sort of compelled by people who are beyond the law– It’s sort of a vicarious thing.

Without spoiling too much, who is your favorite character from “Man on the Run” and will we find them hard to love at first?

Oh yes. Let me give you some background. I wrote a book called “Second Story Man,” and it was about a master burglar named Francis Hoyt. And I got the idea because I’m a little dismayed by this country’s fascination and obsession with winning and being the best. I don’t think it’s particularly healthy. We make TV shows into contests so there’s a winner and a loser. So, I wanted to create a character who is like that, [who] thinks he’s the best and is arrogant and behaves that way. And then what are the consequences?

Spoiler alert, at the end of the book, somehow, I won’t say how, Hoyt gets away with it. He walks away even after being caught in his crimes. So, I wrote another book called “Canary in the Coal Mine” and now Hoyt continues on as a fugitive. What will he do now? And that’s where this book starts.

Where does he go? What will he do? I always meant for Hoyt to be a despicable character that you don’t really like. You wouldn’t want to be best friends with him and yet he’s compelling. You can’t take your eyes off him because he thinks so differently. So for me, that’s also the scariest character in there because he will do anything to win.

Sometimes you like the writing, but won’t like the character. Truthfully, I don’t want you to. I just want you to be interested in him. It’s my job as a writer to take characters who are unlikeable and make them compelling enough that you want to read on and find out what happens to them.

You are notorious for stating that you “never use an outline” when you begin a new novel. Is this any different to what you would preach to Hunter students in your teaching years?

No, what I would tell my students was to find what works best for them. I really don’t believe in telling people to do it a certain way because I think everyone has to find their own way. So for me, it works. But there’s an author named Jeffrey Deaver who does a 100-page outline before he even starts. I could never write that way. For me, it’s self-discovery. I just think that everyone should find what makes them comfortable in the best way they can do it.

What advice would you give to an aspiring writer at Hunter reading this article right now, about getting started in the crime writing world after college?

First of all, you don’t have to commit a crime. And you don’t even have to know a criminal. You just have to be in touch with that bad side of your own psyche. In all seriousness I would probably do what I did– when I decided to write a crime novel– I just read every crime novel that I could get my hands on. Classics, like [by] Raymond Chandler, I would just read them until they kind of soaked in. The “what to do” and “what not to do.” That would be my primary suggestion.

The other thing is to make a whole list of crimes. Every crime you could possibly think of. By the way, there aren’t a lot of dead bodies in my books because I think there are plenty of other crimes that are just as interesting and more relatable to people. But, make the list of crimes. Then, make a list of where it might take place. And then a list of who is going to be investigating the crimes– is it a detective? Is it a cop? Is it a lawyer? Is it a reporter? Then, you just have to come up with compelling characters and a plot. So, my main suggestion here is to read as much as you can, and not only crime novels, all novels!

Your collaboration with Prison Writes – a program that works closely with those incarcerated to teach them about writing – is awe-inspiring. Is there a special piece about your experience there that you now carry with you in your writing?

I think we carry everything that happens to us, but yes. I had the privilege to visit a prison in upstate New York called Otisville. It’s a federal facility that’s really not high-security. Forty guys showed up for the class, and nearly all of them had brought some piece of their own writing in journals and that was very inspiring.

This makes me think, there’s very little difference between you and me, and people who wind up in prison, other than their circumstances. They’re human beings. And it makes you wonder, how did this person wind up in there? My point is, just because someone is in prison doesn’t mean they’ve dropped out of the human race.

Leave a Reply