For many students, attending a CUNY school largely depends on factors like affordability, familial obligations, and other commitments that bind them to the city that never sleeps.

Enrolling at CUNY offers a feasible means to balance academic and personal responsibilities, in a city that provides ample opportunities for practical work experience and financial stability. However, this convenience comes at a cost. The sky-high cost of campus housing, which at Hunter is almost double the tuition, leads most students to rely on public transportation for their daily commute to and from school, adding an extra layer of complexity to their already busy lives.

Commuting to college in New York City is far from a walk in the park. Navigating the daily journey through the city presents daunting challenges, with subway safety being a primary concern.

The city’s rising crime rates and the millions of people navigating its vast transit system create a palpable atmosphere of unease. For students traveling from various boroughs, and outside the city from Long Island or New Jersey, their daily commute to school can be arduous and time-consuming. They often have to take multiple trains or buses, sometimes spending hours in transit, even without accounting for subway delays, which have risen 30% since 2023.

Acts of theft, harassment, and other forms of unwarranted aggression are unfortunately common within the transit system, leaving students and other commuters feeling unsafe and vulnerable. While subway crime has slightly gone down, with 538 subway crimes committed between January and March 2024, so has ridership on the MTA, which has seen a decrease of 2 million riders since 2019.

This spate of subway violence, as well as an incident last year at Hunter’s own subway station, serves as a stark reminder of the pressing need for improved safety measures.

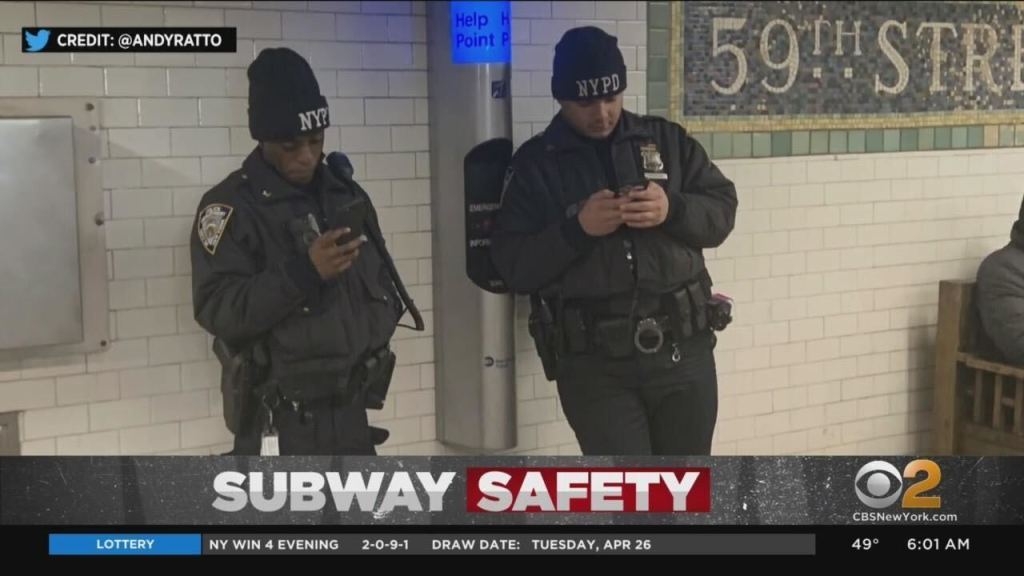

Despite the police presence in subway stations intended to provide a sense of security for commuters, concerns persist, particularly for students who take evening courses or participate in extracurricular activities that require them to commute at night. The inattention from the NYPD has been noted on social media, with officers being preoccupied with personal activities, such as using their phones, chatting amongst themselves, or focusing on minor issues like fare evasion, rather than actively ensuring the safety of passengers.

“I don’t necessarily have beef with the police. I don’t mind them,” said Osa Noyigbon, a male student from City Tech., “Of course, they’re there to serve. But in reality, it just looks like they’re there to intimidate.”

Similarly, Baruch student Kiarra Boodram expresses her doubts on the effectiveness of the NYPD in MTA stations.

“I’m not going to sit here and say the police are necessarily doing anything to protect my safety,” Boodram says. “Oftentimes when I see cops, especially in bigger stations like 23rd Street or Grand Central or wherever I have to go, they’re at the turnstiles or meters. Are they on the platform necessarily protecting people? No. Sometimes they’re on the train, but it’s never like anything’s really being enforced.”

In response to the escalating safety concerns, Governor Kathy Hochul announced in March the deployment of the National Guard and state troopers into the city’s subway system, along with the implementation of mandatory baggage checks at stations throughout the city. While these measures are intended to enhance passenger safety, their presence can be taxing, and many still don’t feel secure. This heightens feelings of vulnerability, especially for women, Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC), and queer students who may face additional profiling and discrimination. Community organizations like Safe Walks NYC have played a vital role in promoting commuter safety and advocating for the needs of marginalized communities.

However, despite these efforts, the root causes of violence in the subways remain unaddressed, and the narrative surrounding these incidents often oversimplifies the issue. There’s a public misconception that these acts of violence only arise from migrants, unhoused people or those who struggle with mental illnesses. But in reality, subway violence can originate from individuals who are comparatively more fortunate, and the mere presence of police does not provide sufficient relief, as evidenced by the murder of Jordan Nealy in May 2023.

“Incidents happen on an almost daily occurrence. There are people always hanging around the station despite the police,” Noyigbon says. “Whether you know there’s a homeless crisis or not, the biggest threat to commuters on the subway will be commuters themselves.”

It is crucial to address these safety concerns comprehensively, rather than solely focusing on issues related to individuals with mental illnesses or the unhoused population in transit stations.

Beyond safety concerns, students also contend with challenges stemming from fare hikes and the high cost of transportation.

Unlike NYU, Columbia, and a few other universities that offer free shuttle bus services, most CUNY students rely on public transportation and lack access to safer options. In addition to taking the subway, some students must take the Metro North, Amtrak, NJ Transit or Long Island Railroad, where fares can range from $5 to $16 per ride.

Hunter College student, Adilene Diaz Torres, voices her frustration over the limited resources available to CUNY students, like a student Metrocard, which is available for other students attending public institutions in NYC.

“At least if they give a student discount, that would be okay,” Diaz Torres says. “If they don’t want to give it to us for free, then I’ll settle for a discount. But I think it makes zero sense that they want to hike it up to, what? $3, when that adds up and people are continuously getting killed [on the MTA].”

Students find themselves shelling out hard-earned money for transportation without any guarantee of efficiency during their daily commute. Diaz Torres shares her experience of being late due to subway delays, which resulted in her missing class. Delays resulting from inadequate scheduling, ongoing construction, or violent incidents and altercations only add to the frustration.

Moreover, accessibility emerges as another crucial issue for commuter students in NYC, especially those with disabilities.

Boodram, who deals with cerebral palsy and uses mobility aids like crutches and a wheelchair, underscores the need to reallocate funds from fare evasion and hostile architecture to improve accessibility.

“All the money that they’re kind of skating on for fare evasion, and hostile architecture should be reinvested into things like elevators and ramps,” Boodram says.

She also emphasizes the significance of maintenance, noting that although the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) legally mandated public transportation accessibility, many subway stations have outdated architecture hindering effective renovation. Furthermore, she notes the difficulties caused by staircases in newer stations like Hudson Yards and stresses the consequences of elevator or escalator malfunctions.

“I think the city has a major issue with prioritization because they’re focusing a lot on aesthetics and commuter volume, rather than how commuters are going to benefit with the infrastructure of these stations,” Boodram says.

The lack of accessibility in New York City’s train stations compounds the challenges faced by commuters with disabilities. Even stations with accessibility features often fail to function properly, worsened by constant construction and crowded rush hour conditions. Additionally, the removal of seats from certain trains and unusable benches at stations worsen the discomfort faced by commuters, particularly those with mobility impairments.

To tackle these pressing issues, a collective effort from governmental bodies, MTA leaders, and educational institutions is imperative. Policymaking and resource allocation must prioritize the safety of commuters, the fiscal sustainability of the transportation system, and accessibility for all riders. Addressing the root causes of violence and investing in social services can also alleviate pressures faced by marginalized communities, benefiting all commuters.

Improving accessibility in public transportation is non-negotiable for ensuring equity and inclusion. Allocating funds to renovate stations, install elevators, and address hostile architecture is paramount. By incorporating insights and suggestions from CUNY students, we can take tangible steps towards a more inclusive transit system, alleviating the stress of subway travel.

Proposals like the Fix the MTA bill, which aims to address the MTA’s funding shortfall, improve service quality, increase accountability, and ensure that public transit serves all New Yorkers as a vital resource, are crucial in tackling the systemic issues plaguing our transit system. In addition to these efforts, advocacy for free or reduced fares, alongside financial support for students, must be championed at both city and state levels. Organizations like NYPIRG, initiatives like the New Deal for CUNY, and the expansion of the ASAP program, can provide much-needed relief for students struggling with the cost of commuting.

As of recently, eligible NYC public school students will receive OMNY cards valid 24 hours a day, year-round instead of MetroCards, starting this 2024-2025 school year. Building on this progress, we should extend this benefit to CUNY students, providing them with the same convenience and affordability.

CUNY leaders must actively advocate for their students’ well-being, fostering collaboration with transit agencies to devise innovative solutions tailored to students’ needs. By expanding these programs, we can help ensure that all students have equal access to affordable transportation, regardless of their institution or level of study.

It’s time for concerted action to transform the commuter experience in New York City. By listening to students and implementing their insights, we can build a transit system prioritizing safety, affordability, and accessibility for all. Let’s continue to pressure our leaders to take meaningful steps towards creating a better future for commuter students, ensuring they never have to compromise their safety for their education.

Leave a Reply